ABOUT OUR STORY

by: Susan Sutton

Citizens of Concordia, Kansas, have long been interested in live theater and entertainment.

The first traveling troupes came to town on the Missouri pacific railroad in 1876 and stayed at the posh Baron’s House Hotel south of the depot. These professionals, en-route from Denver, St. Louis, or Chicago performed for Concordians at LaRocque Hall built in 1877.

This multipurpose theater and hall, a functional but unadorned and cramped facility still stands at the comer of Broadway and Sixth streets.

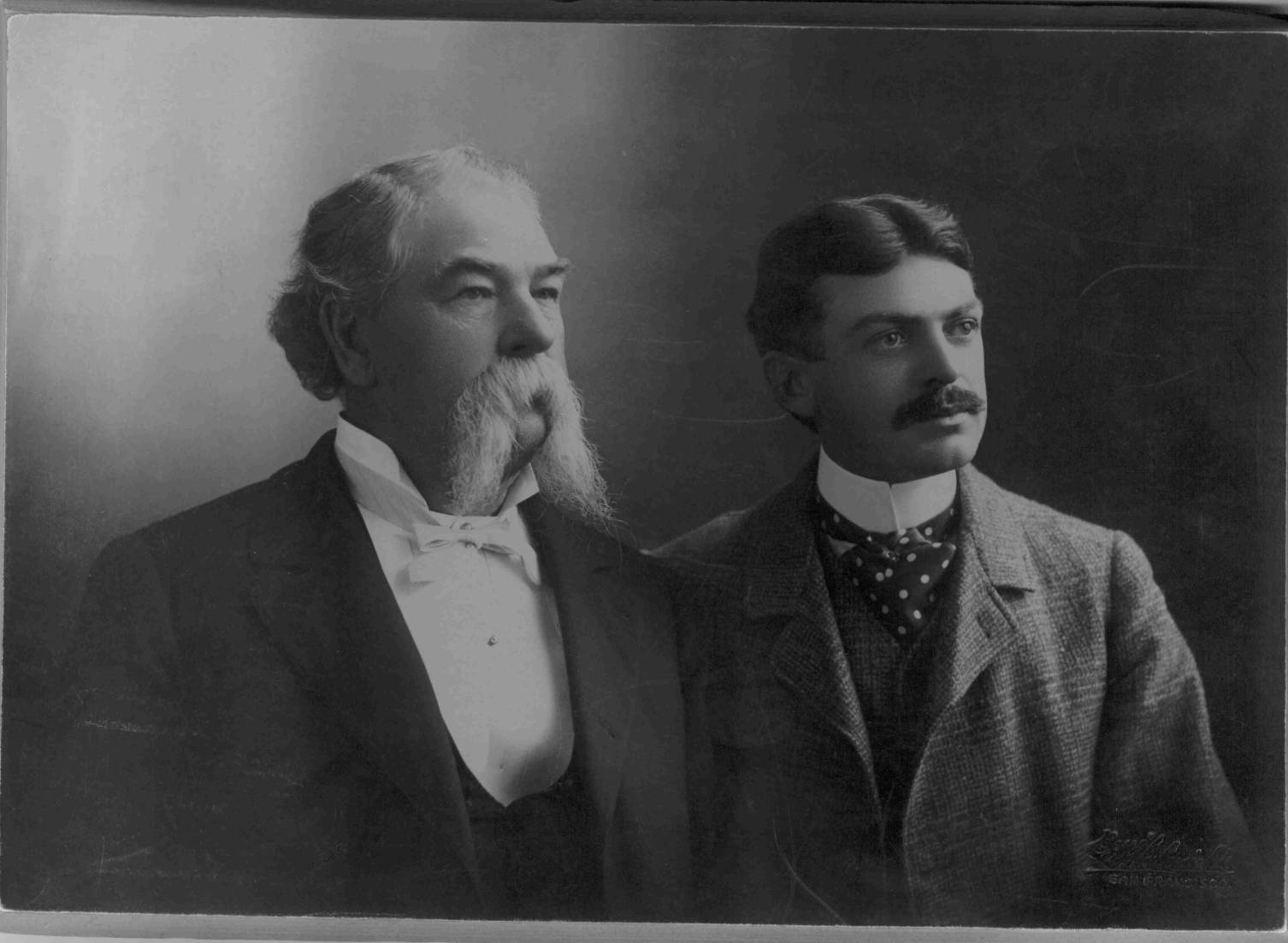

At the turn of the century, Concordians realized the need for a larger, safer, more modern facility to accommodate the fine traveling shows playing to burgeoning audiences. Fortunately, for the taxpayers and city officials, municipal funds would not be needed. A colorful businessman from the community by the name of Colonel Napoleon Bonaparte Brown had plans of his own.

After arriving in Concordia in 1876 from Missouri with a rumored suitcase full of money, his beautiful Bostonian bride, Katherine, and a thirst for fortune, Napoleon, who had served terms in both the Missouri and Kansas legislatures, took up residence in Concordia and awaited the arrival of new settlers who needed to borrow money.

With the establishment of the bank and its proper, but high, interest rates, Brown soon took his place among Concordia’s wealthiest elite. The self-entitled Colonel owned the finest home in town, Brownstone Hall, which can be seen today at the west end of Sixth Street.

Construction Begins

In November of 1905, Colonel Brown announced to the townspeople his plans to build a fully outfitted opera house for Concordia. His generosity may have been prompted, in part, by the news that the nearby towns of Beloit and Lincoln were planning large, new opera houses. The construction of the theatre was to be under the direction of Brown’s son, Earl Van Dom Brown, who soon after toured more than thirty opera houses in Kansas and others in Missouri, gathering ideas. Native Concordian W.T. Short, already known for his work on Brownstone Hall and other fine buildings was chosen construction supervisor.

Renowned Kansas City theatre architect Carl Boiler was hired to prepare the design drawings and the blue prints. Local laborers were hired and construction got underway.

Ground breaking ceremonies took place on April 3, 1906. Local newspapers carried daily progress reports while townspeople and sidewalk superintendents alike watched with interest as the sixty foot high building took form.

Throughout the building process, the Browns stressed the use of local resources: labor, native limestone from a local quarry, and locally fired bricks.

At its completion, The Brown Grand Theatre stood sixty-feet high and spanned one-hundred- twenty feet in length. Renaissance in style and overall design, the $40,000 structure became a priceless jewel amid rare aesthetic fiches in a small town in turn of the century mid-America.

Opening Night

The formal opening of the Brown Grand Theatre took place September 17, 1907. In the words of Carl “Punch” Rogers who was in attendance on opening night, “The firemen who were at the doors were in full uniform and the ushers at the door wore white gloves. I’ll tell you, that night society sort of quivered. It was all beautiful . . . yes it was.”

New York’s Joseph M. Gaites Company presented the musical play The Vanderbilt Cup. The production had played eight months at the Broadway Theatre in New York and three months at the Colonial Theatre in Chicago. The Harry Steinberg Orchestra from Topeka accompanied the singers and action from the orchestra pit. The highlight of the play came when two vintage racing cars appeared to be speeding along at one hundred miles per hour. This effect was achieved by revolving painted scenery behind two cars. As the background flashed by, stagehands, pulling cables attached to each car shifted their positions as each driver appeared to be jockeying for the lead.

The Vanderbilt Cup Race, which was held first in 1904, ran for ten years. As the event became more popular for New Yorkers than the World Series, it had to be discontinued in 1914 because police were unable to restrain the Crowds – some numbering half a million – from risking their necks on the dirt highway just to catch a glimpse of the cars speeding by at up to sixty-four miles per hour. The popularity and social importance of the race is chronicled in the play. One scene shows two touring cars filled with elite businessmen and chorus girls setting out with well-laden hampers full of food and wine – in essence, the makings of a tailgate party.

Ownership Changes

The Brown Grand, hailed as the most elegant theatre between Kansas City and Denver, unfortunately reigned supreme for only a few years. Fatefully, both Colonel Brown and his son Earl Brown were dead within four years of the celebrated opening of the theatre.

Subsequently, the ownership of the theater was passed to the widows, neither of whom was overly fond of the other. Soon neither Katherine nor the younger Gertrude, wished to be burdened with the complex operational duties, so a contract was drawn up to present the theater to the city of Concordia as a memorial to the Brown family name. The arrangement was short-lived however, and by 1915, due to financial necessity and the decline of suitable roadshow fare, the Brown Grand was returned to the family estate.

For the next ten years, the theater came under the management of Ray Green, editor of the Concordia daily newspaper, the Blade-Empire. Mr. Green had married Gertrude, Earl Brown’s widow, a talented designer and decorator in her own right.

Live Entertainment

From 1915 to 1925, the Brown Grand Theater played host to a variety of entertainments. Road shows with famous stars made a return to the bill of fare. Renowned Bohemian songstress Madam Ernestine Schumann Heink, respected New York actress Laurette Taylor and world famous dancers Ruth St. Dennis and Martha Graham were among the many well known of music, dance, and theatrical world to play the Brown Grand during these years.

Widely diverse entertainment included concerts, plays, recitals, local high school graduations, minstrel shows, operas, wrestling matches, speeches, local theatre productions, and some exciting examples of the newest fad sweeping the country – moving pictures.

The Film Years

In 1925, the Concordia Amusement Company purchased the theater for a movie house. Movies had wrought irreversible havoc on live theater throughout the nation. Inevitably, the Brown Grand suffered the same plight as thousands of theatres across the land.

In a positive attempt to keep abreast of the changing tastes in entertainment, Carl “Punch” Rogers, who as a young man had attended the theater’s opening, succeeded Ray Green as the part owner-manager. As an affiliate of the Fox Midwest Theater Company, house and stage were refitted for motion pictures and a few years later in 1929, for talking pictures. Several remodeling and refurbishing over the next thirty years brought the installation of a movie marquee, an air-conditioning system, a fire projection booth, and a wide-screen, among others. The Ladies Lounge was converted into a concession stand. At this time, a complete paint job covered the original green, white, and gold color scheme. In 1955, in its last remodeling as a movie house, the theater was painted pink and blue with silver accents.

For nearly fifty years, the theater continued to operate as a movie house until the last picture show September 10, 1974, a premier screening of The Devil and Leroy Basset, written and directed by Concordia filmmaker, Robert Pearson.

Restoration Effort Takes a Step

Shortly after the Concordia Centennial in 1971, the Brown Grand Theater was recognized as a National Historic Building and was listed as such in the National Historic Register. The official date was July 26, 1973. Soon after, Everett Miller approached the owners of the Brown Grand Theater, Jack and Hanalesa Roney with the idea of purchasing the theater for the purpose of restoring it. The Roneys bought the theater from the Concordia Amusement Company in 1968. Already recognized as a National Historic Site, the theater’s restoration was selected as a community Bicentennial Project. Funds were raised, a contract drawn up, and the theater was purchased.

Once the Brown Grand was purchased, it was given to the City of Concordia and then leased back to the newly formed Brown Grand Opera House Inc., to restore and operate. The first large- scale organized fund raising campaign, “Lend a Hand to the Brown Grand,” was kicked off on October of 1975. Nearly $250,000 in cash and pledges was raised in this drive.

The restoration of the Brown Grand was divided into two Phases: Phase I was essentially the restoration of the exterior, and Phase II, the interior. Mr. Hillary Wentz, local retired contractor with engineering experience, volunteered his services for both phases of restoration.

After conducting a series of telephone conversations that led him to countless individuals in five states and twice that many dead ends, Jack Roney finally located architect Carl Boller’s original blueprints of the theater. These proved invaluable throughout the restoration process.

Restoration: Phase I

Phase I officially began in August of 1976. The movie marquee was removed as was the thick-walled projection booth. Rotting ceiling trusses were replaced and a new roof was installed. The front edifice was repaired. Side entrance doors, which had been covered over and transformed into movie bill showcases, were restored. Additional native limestone needed to re-form a central column between the two main entrance doors came from the ruins of a guard tower located at a World War II prisoner of war camp several miles north of Concordia. The solid oak front doors are exact copies of the originals.

Phase I of the restoration continued with brick and stone tuck-pointing, sandblasting, and re-coloring of the bricks, trim painting, cement improvements, and the installation of an additional fire escape to bring the theatre into compliance with safety regulations. With the hanging of new guttering and glazing of new leaded glass panels, Phase I of the restoration was completed. The exterior looked now as it did on opening night, September 17, 1907.

Restoration: Phase II

Phase II of the restoration began in May of 1978, nearly two years after Phase One began. During those two years, the theatre remained in use for community theatre productions and other theatre events. However, with the start of Phase II, the theatre was officially closed. The theatre seats were removed to make room for the large timbers that were laid down to level the sloping main floor so that a forty-foot high scaffolding could be erected.

The interior restoration began with the opening up of several closed stairways. All crumbling and disintegrating plaster, lathing, and studding were replaced. Five dusty dressing rooms were modernized with lighting and plumbing fixtures. The original stage lighting system with its hazardous resistance-type dimmers was replaced with a more modem portable system. New lighting instruments were added above the stage and in a newly formed ceiling cove above the theater auditorium.

In the basement, a concrete floor was poured over the existing dirt floor. Backstage, the veteran pin rail, located twenty feet above the stage floor was left in its original state. The pin rail is used to secure the ropes used to fly the scenery; four original painted backdrops are still used today.

During the backstage restoration, playbills from plays that appeared at the Brown Grand Theatre from 1910-20 were discovered behind tarpaper on both sides of the proscenium. These playbills were carefully removed. Today eighteen playbills are framed and mounted on the walls of the balcony foyer.

As Phase II continued, fresh plaster replaced old. Ornate plaster moldings were repaired or replaced around the proscenium arch, around the box seats, and in the vaulted ceiling. White and green paint restored the original color scheme, which was completed with the addition of lavish gold leaf stenciling in three patterns and accenting on decorative molding.

Theatre seats donated by Bethany College of Lindsborg, Kansas were remarkably similar to the originals. These were reupholstered in rich green velvet. Draperies sewn from the same dark green fabric were hung at the windows and in the box seats. Specially dyed green carpeting was laid on stairways, patron walkways, in the balcony foyer, and the Ladies Parlor. The Ladies Parlor was restored with new plaster, paint, wallpaper, woodwork, and renovated fireplace. Photographs of the Brown Family completed the period flavor of the room.

In all facets of the restoration, every effort was taken to duplicate or restore each detail of the building’s originality. Brass railings accented balconies, box seats, and orchestra pit. Brass lighting fixtures added period sparkle to the lobby, balcony foyer, stairways, and original maple box seat chairs were re-caned and refinished. The lobby received a long overdue face lift.

Napoleon Curtain

On opening night in 1907, Earl Brown, son of N.B. Brown, unveiled a magnificent drop curtain reproduction of a Horace Vemet painting. The curtain, entitled “Napoleon at Austerlitz,” was presented as a gift to Colonel Brown from his son in recognition of his father’s contribution to the community and to the Brown Grand Theatre, his crowning achievement.

The original curtain, which still hangs above the stage, saw little use during the theatre’s motion picture years. A 1967 tornado caused extensive water damage to the roof over the stage. The rain that accompanied the tornado permanently stained and streaked the already faded and brittle painting.

Taking an extreme interest in the Napoleon curtain, Mrs. Marion Cook, member of the Brown Grand Board of Directors, donated a new drop curtain at a cost of $8,500. The new curtain was painted, surprisingly enough, by the same firm that had painted the original: Twin City Scenic Company of Minneapolis, Minnesota.

For the artistic work on the drop, sought-after scenic painter, Robert Braun, was hired to do the Napoleon battle scene, and Michael Russell, President of the company, came out of retirement to paint the bordering green draperies and gold and bronze frame around the picture.

The two artists requested a color photograph of the original Vernet work “Battle of Wagram” which hangs in the Hall of Battles in the Palace of Versailles near Paris. After a few failing efforts, Mrs. Cook finally obtained the needed photograph and it was sent to Minneapolis.

After several months’ time, the new curtain, funded by the Cook Foundation, and presented to the Brown Grand Theatre as a memorial to Charles S. Cook, was unveiled. On January 7, 1979, an expectant public saw the dramatic painting raised from the floor of the stage and into its present position.

1980 Reopening

Preparations for the reopening of the Brown Grand Theatre began in early 1980. The Brown Grand Board of Directors made the decision to restage the original opening night play, The Vanderbilt Cup.

The script was located on microfilm after some extensive searching by board member, Peggy Doyen, at the Library of the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, in New York. The music, some original to the show, some standards of the period, was assembled by Dr. Everett Miller, director of music at Cloud County Community College and vice-president of the Brown Grand Board of Directors.

Dr. Miller also obtained a copy of a one and one-half minute film clip from the Library of Congress showing an actual Vanderbilt Cup race featuring Barney Oldfield. The race was filmed on Long Island, New York in 1906. This early racing footage was subsequently shown on a movie screen over the stage during the race sequence in the play, accompanied by enthusiastic cheers and shouts from the audience.

Reopening night was the most electric theatre gala since the Theatre’s opening seventy-three years earlier. Three women, Winifred Hanson, Pauline Kennett, and Verl Turner had attended the opening of the theatre in 1907. Over seven decades later they sat front row center for the reopening.

Other patrons and dignitaries, many dressed in period costume, paid twenty-five dollars a seat to view the community production of The Vanderbilt Cup. A photograph of the audience was taken at intermission to record the historic moment. Leon Gennette, executive vice-president of the Chamber of Commerce and president of the Brown Grand Board of Directors, gave a short speech thanking the 750 people and organizations who contributed to the restoration.

At play’s end, the thunderous applause seemed the greatest reward for eight years of sweat and tears, financial worries, missed deadlines, and uncertainties. The restoration was at last a reality! Theatre had come alive again in Concordia, Kansas.

Board member Peggy Doyen pointed out the greater significance of the second production of The Vanderbilt Cup by saying that only one man had been responsible for the building of the theatre and that a touring company from New York had performed the play. “This time around, however, the entire area was involved in the restoration, and several hundred volunteers helped with the play. This time the community was involved in the opening.”